For four days in June 1947 it seemed like Llangollen was the only place in the world. You can see and hear it captured in the Movietone newsreel, a precious 11 minutes. You can read the programme, too.

33 choirs came, from 11 countries. In addition to the four UK nations Denmark, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden and the Irish Republic were represented. There were late cancellations from Belgium, Switzerland, and Spain.

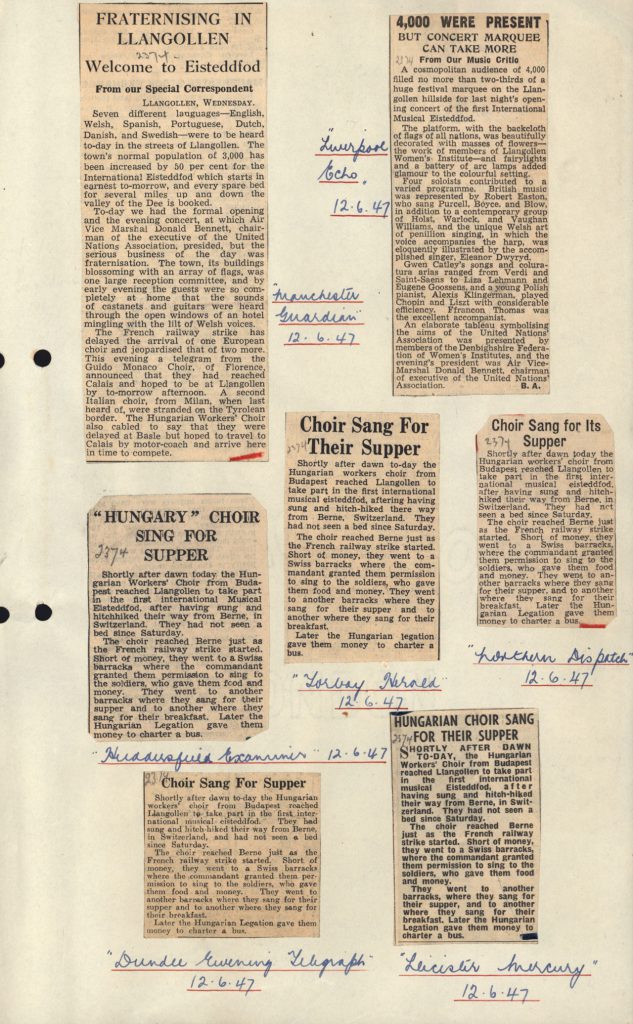

They made memorable journeys: quietly from Kalmar in Sweden, the madrigal choir the first to arrive; colourfully from Porto on Portugal’s Atlantic Coast, five days on the road, driving down Castle St in a red and green bus as townspeople capered a welcome; happily, by ferry from Dublin, with a big send-off at Dún Laoghaire; slowly, like the winning male voice choir from Budapest, giving concerts to raise travel money as they hitchhiked across Europe, their travel plans disrupted by the rail strike in France; arriving too late to compete, the similarly delayed Citta di Milan choir sent regular telegrams as they got nearer Wales.

The winners of the choral competitions were:

- Mixed: Sale and District Musical Society (England)

- Female: Penarth Ladies Choral Society (Wales)

- Male: Hungarian Workers Choir, Budapest (Hungary)

- Young Peoples: Kirkintilloch Young Peoples Choir, Glasgow (Scotland)

- Childrens: Snowflakes Children’s Choir, Cardiff (Wales)

Local talents included the Collen Ladies Coir from Llangollen, and girls and mixed versions of the Coedpoeth Youth Choir.

In Llangollen by invitation, two troupes of Spanish dancers from Seville and San Sebastian performed on the stage and on the town streets; their performances changed the Eisteddfod.

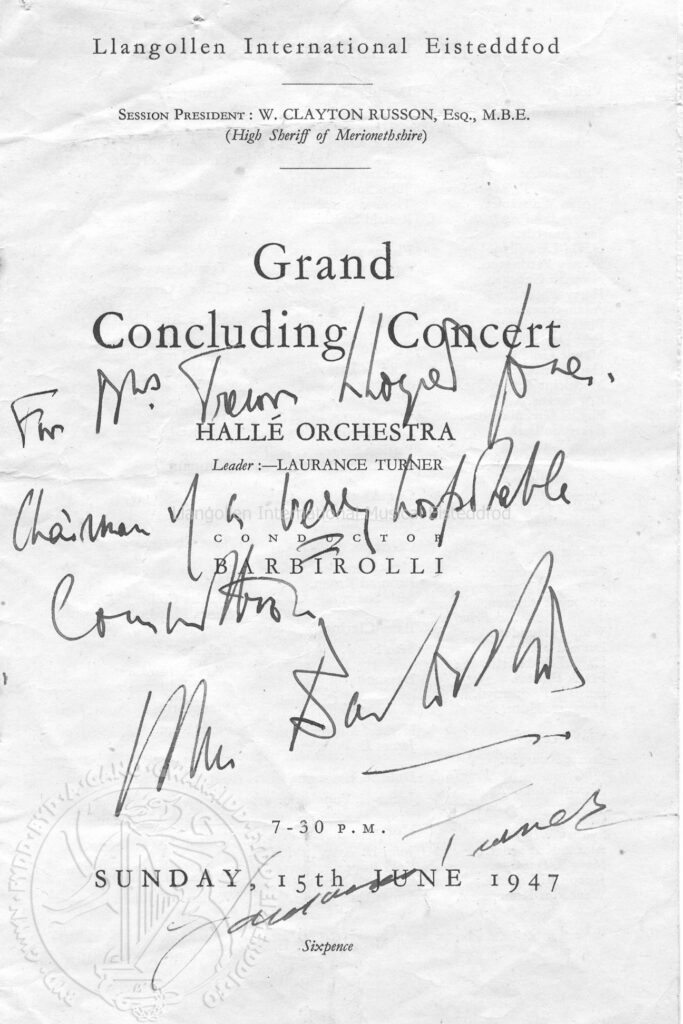

The audience packed the field for every session, up to ten thousand at a time. There were three full days of competition from Thursday to Saturday: the choirs sang their national anthems before the test pieces. The evening concerts featured mainly the choirs and some guest soloists from Wednesday to Saturday, concluding on the Sunday with the Halle orchestra under Sir John Barbirolli; they played Weber, Dvorak, Mozart, Delius and Richard Strauss. The singing went on for hours in the houses, hostelries and hotels.

There was more than singing, dancing and mingling. Ecumenical services were held in Valle Crucis Abbey, including the first (official) Catholic High Mass since the Reformation. Trappists from Caldey Abbey processed chanting plain song. The visiting choirs from Catholic countries sang hymns. On stage, branches of the Women’s Institutes from around Denbighshire combined in a pageant showing 20 folk costumes from round the world.

Journalists from up to 100 international, national and local newspapers wrote stories about the competitors, the organisers and the town, and reported the results, including detailed adjudications. The BBC broadcast performances and interviews to a dozen countries. Movietone news captured the spirit of the thing. The results were printed even in the New York Times. Mr Churchill sent a congratulatory telegram.

Welsh choirs, including local ones, did well in mixed, female, young peoples and children’s competitions. But the absence of Welsh male voice choirs is a mystery. After all, three men’s choirs from England turned up, and so did four Welsh ladies choirs. Explanations have been proposed over the years: fear of having their quality exposed; the limits set on choir size were too low; costs of doing both the National and International Eisteddfodau; even active discouragement by the National Eisteddfod, whose concerns about the lusty upstart festival are documented in archived correspondence. Best to leave all that to the conspiracy theorists, and instead celebrate the famous Froncysyllte Male Voice Choir, founded in 1948 partly to rectify the omission.

Before the festival ended, the President Clayton Russon and Chairman George Northing announced to the press that Llangollen would hold a second international eisteddfod in 1948. This triggered an unexpected row, and a leadership crisis. Harold Tudor wanted the International Eisteddfod he conceived to move around like the National, and tried to enlist public support through the press, to immense protest in Llangollen. The resolution was an agreement that the festival would stay in Llangollen as long as it was capable of putting it on. In a few short months Russon, Tudor and Northing all left the Eisteddfod.

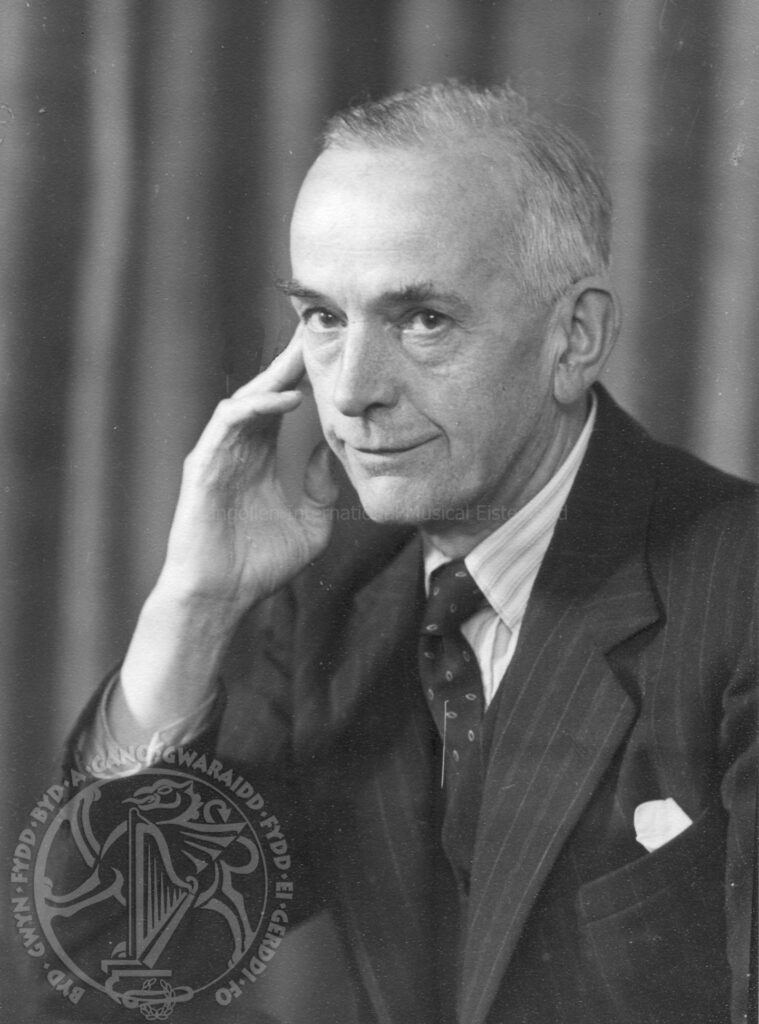

Supported by the rest of the organising committee, the calming presence of Vice-Chair Jack Rhys Roberts ensured the survival of the festival; he was Chairman from 1948 until his death in 1970.

But we should not dwell on troubles. At the time, everyone was full of praise for Llangollen.

Someone said:

“That it was possible for such an event to take place at all in any place within two years of the end of world-wide hostilities was, to say the least, impressive but that it should occur through the work of the local council, on an improvised stage, in a canvas auditorium, erected on the recreation ground of a small, tranquil, picturesque town in North Wales was perhaps something of a minor miracle.”