The Unarmed Road of Flight: Refugees and the Eisteddfod

Chris Adams and Barrie Potter, Archive Committee

With the roads of Europe once again crowded with refugees from conflict “on the unarmed road of flight”, it seems a good time to remind ourselves that many of the competitors who have delighted us during 75 Eisteddfod weeks have been people displaced from their homeland, sharing their culture, music and dance as a way to affirm their culture.

The UK’s Ukrainian communities expanded greatly after the war, and for four decades from 1950 brought their athletic and acrobatic dances to Llangollen. They were celebrated in Dylan Thomas’s 1953 radio broadcast: “Ukrainians with Manchester accents gopak up the hill.” They came not just from Manchester, but from Bradford, Reading and other UK towns. By the late 1980s they shared the field with troupes from Ukraine homeland itself. In July 1987 when ITV’s Treasure Hunt dropped into Llangollen the clue for Anneka Rice to find was hidden in a Ukrainian dancer’s boot. Since then some fifty groups from the Ukraine have appeared on our stage, more than any non-UK country in the same period. Kyiv, Lvov, Kharkiv, you name it…they’ve come from every city that has been attacked during the Russian invasion.

In 1991 Turkish Kurds arrived, a young dance group led by Huseyin Cicek, laden with walnuts, dried apricots and salty cheese; the Eisteddfod programme agreed that they represented non-existent Kurdistan (later Cwrdistan). They quickly became favourites: we could share their high-spirited enjoyment not just of their Kurdish costumes, music and dances but also their leaning towards Western culture with its pop music and football. They won many prizes.

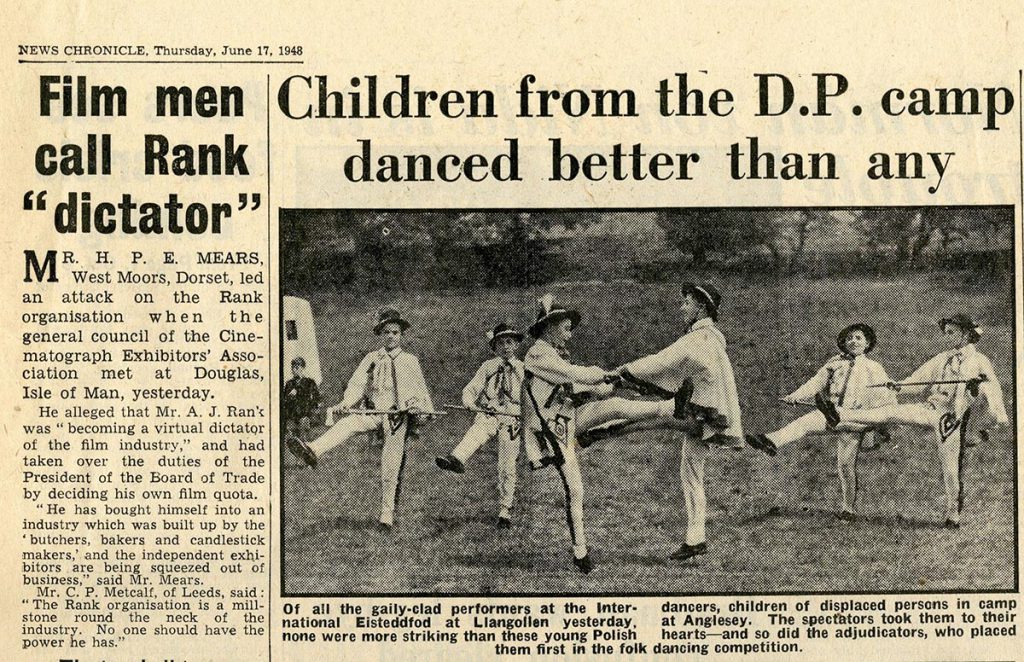

But for the most poignant story, you need to go back to 1948, and the first folk dance competition. It was won by a group of young Polish dancers, teenage boys who from a camp for displaced persons near Beaumaris in Anglesey: they beat two experienced Spanish folklore troupes, and lots of Welsh dancers. We don’t know very much about them: their camp was disbanded a few months after the Eisteddfod, and records have been dispersed. We only the two photographs shown here; the one taken by an audience member shows just how young they were. We often wonder what happened to them and what they took away from competing in Llangollen.

We endorse the Welsh government in its effort to make refugees welcome in Wales. It should be natural for us. Our concept of “hiraeth” embraces the sense of separation from loved ones and the loss of loved connections, the struggle to make a go of it in an alien land. We know too that music and dance can make a valuable bridge between cultures, and between the past and a different future.