The First Honorary Music Director

W. S Gwynn Williams was the first music director of the Llangollen International Eisteddfod and continued in that post from 1947 until he retired in 1977 at the age of 81. He was a musician, composer, and publisher; he also lectured, wrote and broadcast on the history of British and in particular Welsh music; he was very well connected in Welsh musical circles. His influence on the musical life of the early Llangollen Eisteddfod was profound, even dominant.

The son of musician W. Pencerdd Williams, William Sydney Gwynn Williams (1896 – 1978) was born at Plas Hafod, Abbey Road, Llangollen, the house he lived in for his entire life. When he was very young he started playing the piano and violin, and began composing in his teens. At 17 he became an Associate of the Tonic Sol-Fa College of Music in London. From 1922 to 1929 he edited the periodical Y Cerddor Newydd (The New Musician); from 1923 he was Director of Music for the Gorsedd y Beirdd of the Welsh National Eisteddfod; from 1933 to 1957 he was secretary of the Welsh Folk Song Society and become the Society’s chairman in 1957. He was editor of the Society’s Journal for thirty years from 1946. In 1937 he founded the Gwynn Publishing Company with the “aim to increase the repertoire of traditionally-inspired vocal and choral music”.

In August 1945 he encountered the idea of starting an international eisteddfod in Wales at the Welsh National Eisteddfod in Rhosllanerchrugog, through conversations with Harold Tudor. Gwynn Williams was instrumental in conceiving the shape of the future festival, especially that it would be held in a huge marquee, and that it would be held in Llangollen. In many ways he was typical of the professional men who started the Llangollen festival: 50 years old, grey-suited, pipe-smoking, embedded in local and national organisations. His wife Elizabeth Eleanor (“Beti”) was a well-known singer and performed at Llangollen many times.

His formula for the syllabus of the main vocal competitions of the early International Eisteddfod was classical, strictly classical: he specified two songs per competition, the competitors chose a third. The set pieces focussed on old music from the European canon, designed to be sung in several languages, but some were to be sung in Latin, thought tobe equally disadvantageous to all nationalities. He arranged many of the test pieces himself; perhaps half of the choral music over the first 30 years of the festival comprised his arrangements released through the Gwynn Publishing Company. The preference for this type of music was reinforced in the selection of adjudicators. Nevertheless, for most of his time there was a good audience for the competitions, an audience enthralled by the range of voices and vocal styles, willing to sit through 20 or more repetitions of the two specified songs and record their own scores and comments in their programmes. They loved it when he conducted the community hymn singing which filled in spaces in the daytime programme.

He selected a strong set of adjudicators who ensured high standards in the competitions, which were scrupulously judged. They reinforced the preference for his type of musicIndeed in 1953 there was an upset when an American choir was criticised not for the quality of its singing, but for choosing “Oh Susanna” as its third song: “not the sort of music for our Eisteddfod”. In 1971 on the occasion of the 25th Eisteddfod, he wrote: “Looking back, I am glad to think that at no point have we lowered our standards in an attempt to gain some popular or economic advantage. My belief remains unshaken that, if this music festival is to survive, it must continue to insist on the purest interpretation of traditional, authentic folk song and dance, and the highest possible choral standards”.

The role of music director also gave him charge of the evening concerts. Most of these featured selected competitors, released to perform their own choices of song and dance. These were leavened by selected solo artistes, both UK and international, many of them gleaned by agents in London instructed to offer “up and coming” people; perhaps the greatest find here was Placido Domingo with his first British concert in 1968. The opening and closing concerts were different and more spectacular. For the first decade their programme brought in world stars: it was advanced, even avant garde. The Hallé orchestra in 1947 under Barbirolli was the start, but Llangollen got two ballets (Fonteyn and Markova), two operas (including Benjamin Britten’s Turn of the Screw just nine months after its world premiere at La Fenice), and Ram Gopal’s classical-Indian dance fusion from New York. After 1960, driven by poor ticket sales for the advanced offerings, the emphasis shifted to folk song and dance, national groups from all over the world for the opening concert, with the Sunday broadening its scope to more popular events like mass bands.

He built on the success of the first Eisteddfod by helping to found the International Folk Music Council in London in September 1947: The English composer Sir Ralph Vaughan Williams OM became the first Chairman of the new council; Gwynn Williams became Treasurer. Membership of the Council included representatives from Belgium, Germany, Denmark, Brazil, Yugoslavia, USA, France, Greece, Norway, Turkey, Uganda and Switzerland. These contacts were, in all probability, pivotal in assisting the Eisteddfod to attract so many countries to Llangollen.

For 30 years he was “Mr Eisteddfod”; in a very real sense it was his festival. The Eisteddfod commemorated Gwynn Williams with an annual prize and trophy to be awarded for the best folk music performance, but to this day mention of Gwynn Williams can provoke disagreements among Eisteddfod supporters. As the archive record shows, the discord arises from his independent way of working, his making a profit from the festival when all the other workers were volunteers, and the impact of his musical taste on the course of the Eisteddfod. He ran the entire Eisteddfod music department from his house on Abbey Road, preparing the syllabus, seeking and approving competitor applications, hiring concert artistes. In 1947 he was provided with a music committee, which never met and was quickly abandoned. He worked through his Gwynn Publishing Business and received an annual honorarium to cover the expenses; this was increased regularly, usually after a request issued a couple of months before the Eisteddfod. All this was done without producing accounts; neither did he report the profit his company got from publishing the test pieces which W.S. had arranged. Mild resentment from volunteers who freely contributed their time, goods and services was widespread, but only privately verbalised. In 2003 his widow left £300,000 to the Urdd.

We can also speculate around the effect that Gwynn Williams had on the musical focus of the Eisteddfod. A detailed internal review from the early 1980s, written prior to a funding appeal, reports with relief on the recent modernisation of the vocal syllabuses to include 20th century music, a liberalisation process which has continued. But there’s a deeper current. Llangollen missed three musical waves. One in the 1960s made folk music the voice of the civil rights and anti-war movements, an obvious match for the festival’s focus on peace. The second, perhaps a little later, found musicians in Europe and North America embracing and entering collaborations in the music of other continents. The third was the use of amplification and electronics to enhance performance and create new music.

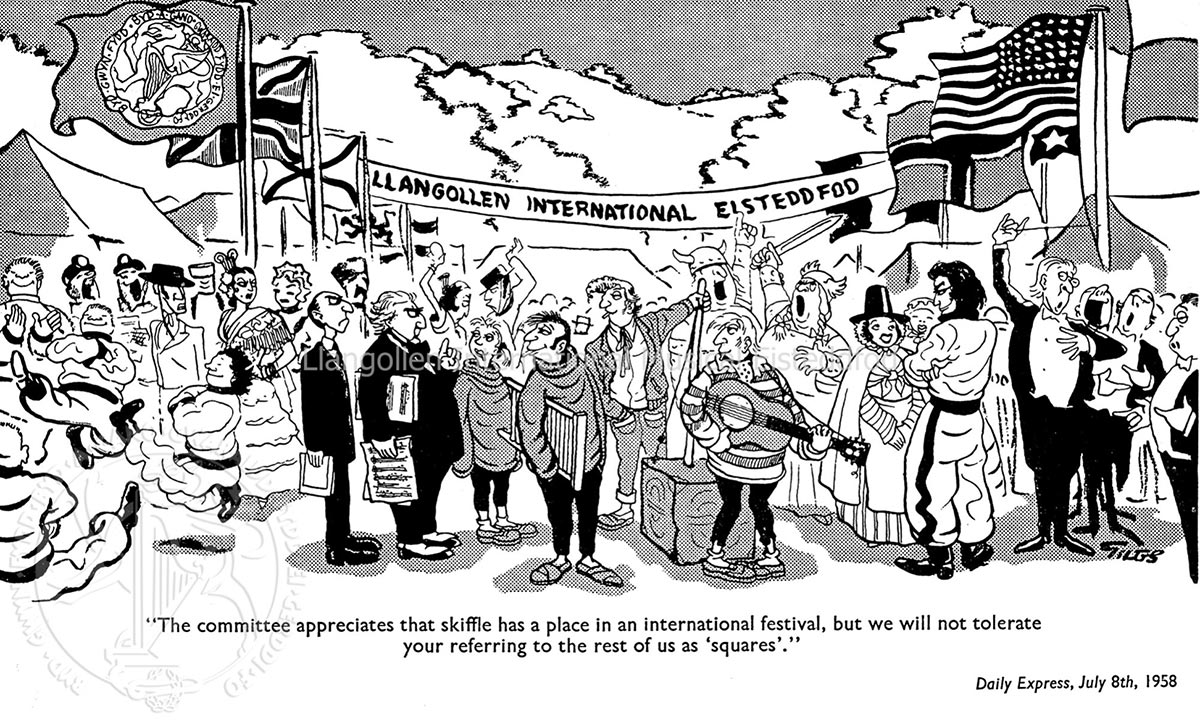

The cartoonist Giles tried to say something about this in 1958, but perhaps more apposite is to see Gwynn Williams as Hogarth’s enraged musician, deeply troubled by all the music being made outside his window.

The cartoonist Giles tried to say something about this in 1958, but perhaps more apposite is to see Gwynn Williams as Hogarth’s enraged musician, deeply troubled by all the music being made outside his window.

With a different vision, Llangollen might have become an early settler in the territory of modern world music, a couple of decades before WOMAD colonised it.

The Eisteddfod Archive contains few records of his work as music director, except for typewritten working lists of the applications accepted. He left us a sheaf of articles written by or about him for magazines and newspapers. For thirty years the Eisteddfod could not envisage doing without Gwynn Williams; it is also likely true that Gwynn Williams encouraged and reinforced this view by his ways of working. Encountering these complex facets of human nature is the sort of challenge which makes the Eisteddfod history so fascinating.

Since 1977 there have been nine honorary music directors. WS was clearly a hard act to follow. The post was abolished in 2019.

© Chris Adams 2023