How the Eisteddfod got its Trophy and Motto

In seeking a high quality emblem and creating a motto the Eisteddfod acted fully in accordance with the corporate spirit of the middle of the 20th century, a time before marketing consultants, mission statements and logos. Inspiration came from the BBC, for example, which had its own coat of arms which included the motto “Nation shall speak peace unto Nation”, based on a Biblical text from the Book of Micah and the Book of Isaiah: “Nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore.”

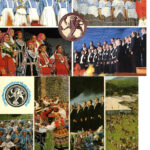

It’s obvious that the Eisteddfod took seriously the design of the trophy, by which the winners would take its message of Peace and Harmony across the world. In 1964 a winning mixed choir from Bakersfield showed their Llangollen trophy to President Lyndon Johnson at the White House, at a time when he was planning a significant escalation of the conflict in Vietnam.

The shield, as its commonly known, was designed by Terence Bayliss Huxley-Jones FRBS, Principal of the School of Sculpture at the Gray’s School pf Art in the University of Aberdeen. The motto in the surround was written by T. Gwynn Jones, CBE, a poet born in Betws-yn-Rhos in Denbighshire, an internationally lauded poet, scholar, journalist and distinguished academic, and a notable pacifist especially during the Great War.

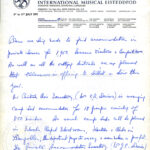

Less well known is how in the Autumn of 1946 the Eisteddfod enlisted these two leaders in their fields to work for the new festival. The initiative was led by Harold Tudor, Publicity Director, and a principal instigator of the Eisteddfod.

Tudor approached two bards to write a motto for the Eisteddfod: the request was for a version in Welsh, with an English translation. First to respond was T Gwilym Jones, the first person to have received all three major literary awards at the National Eisteddfod. He offered a group of suggestions. The right words are there, but the poet doesn’t seem really to feel the artistic and ethical space the Eisteddfod was seeking to create. The Board rejected them rather quickly

Suggestions for Esteddfod Motto by Gwilym R Jones:

| Odled yr holl Genhedloedd i | Let all the nations sing |

| Canwm ac unwn i gyd yghybid | Let us all sing and unite |

| Cyngharanedd rhwng bonedd y dyd | Harmony between the noble ones of the world |

| Gwledd a gân i goledd y gwir | A feast of song to cherish the truth |

| Pob llais yn unllais yn awr | Every voice one voice now |

| Tannau nef i’n tynnu’n un | Heaven’s lyre to draw us nigh |

| Seiniwn gerdd nes uno i gyd | Let us sing a song until we are one |

| Un dynion yn sŵn hen donau | Men are united in the sound of old tunes |

By contrast the selected couplet from the older poet, T Gwynn Davies, perfectly captured the spirit of the Eisteddfod.

Byd gwyn fydd byd a gano. Gwaraidd fydd ei gerddi fo

Blessed is a world that sings. Gentle are its Songs.

It’s fresh and to the point, and works as poetry both in Welsh and in the English translation. The reference to the Beatitudes of St Matthew (Gwyn eu Byd “blessed are”, for instance) was strongly welcomed. So too was the inference in the Welsh version, that a singing world gave forth gentle gardens, deeper by far than the English. But this was the Eisteddfod, after all, and so there was a discussion among the more academically minded in the Eisteddfod community as to whether, despite its poetic success, “gentle” was perhaps too passive to be the most appropriate translation of “gwaraidd” given the ambitious aims of the festival.

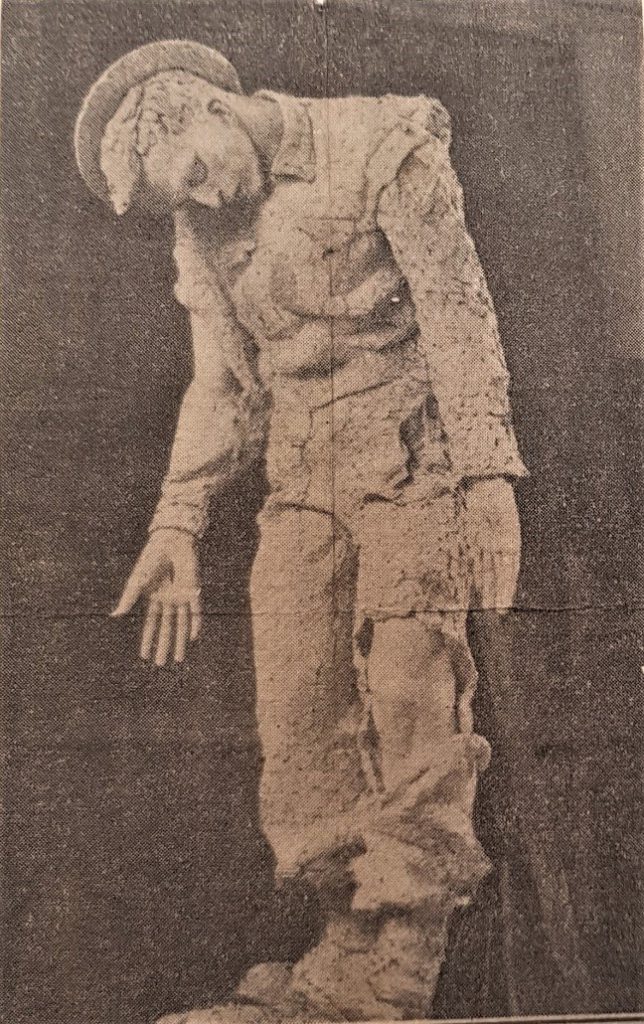

The Huxley-Jones story is a bit more complex. He was born in South Africa, but his mother’s family lived in Summerhill near Wrexham, and as a boy Huxley-Jones had spent school holidays on their estate. In 1946 he was widely seen as an up-and-coming sculptor, but what brought him to Tudor’s attention was a photograph in the Wrexham leader in August 1946 of a sculpture called “Father Forgive Them”, which had been the talking point of that summer’s Royal Academy Exhibition in London. Eight feet tall, it truly captured the exhausted agony of the common soldier. Connections were made with Huxley-Jones family in Summerhill, and he accepted the invitation to design the trophy; a fee of 50 guineas was negotiated. President Clayton Russon provided a general design concept, while Music Director W S Gwynn Williams passed on the lore of the Welsh Harp. Clayton Russon also paid the costs of making the brass moulding. Huxley-Jones visited Llangollen in 1949, and presented his trophy to several winning choirs. He went on to become world famous for several pieces of work, including “Helios” outside the BBC’s Broadcasting House.

For medieval minds, the gryphon, the mythical creature at the centre of the Eisteddfod trophy, represented nobility, courage and determination, qualities demonstrated time and again in the 75 years of the festival. The harp plays to both musical and nationalist sentiments. Encirclement it’s suggested, represent the Gorsedd circle, but there are hints of common representations of the Hindu god Shiva, in his guise as Lord of the Dance. The surrounding couplet gives the context of the search for ways to promote peace, in Welsh only: the rear is left blank.

The image and its associations are so powerful that for most of the 75 years they have acted as the Eisteddfod’s logo. It’s the centrepiece of the stage, and has graced virtually everything from notepaper to first day covers to souvenir autograph books. Silver brooches were commissioned and sold by Friends of the Eisteddfod, and over the years several outside organisations have tried unsuccessfully to steal the design for unauthorised souvenirs. In 1985 the Eisteddfod gave Princess Diana a gold brooch in the design, made by the Royal jewellers.

But the shield isn’t the only way that the Eisteddfod has personalised itself. Taking in our proud stride the 1950s when Dylan Thomas wrote “the best thing that’s happened in Wales” in his Eisteddfod notebook, and the Wales Tourist Board proclaimed “Llangollen – where Wales meets the World”, it wasn’t until 1992 that a new logo was introduced. A multicoloured treble clef appeared in 1992 for the opening of the Pavilion, deemed to be adding much needed colour and life to the event; it survived for about 10 years. In the 2010’s the Eisteddfod was worried about how it compared with other festivals, and flirted for a couple of years with a clipart logo and a strapline announcing that it was unique. Up to 2022, the shield and motto feature in the annual logo for the revived International Eisteddfod.

© Chris Adams, 2022