For most of its 77 years the Eisteddfod has prided itself on being run by volunteers, with a small paid staff. From the outset the idea of doing it ourselves was a part of the organisation’s fierce desire for independence. Professional advice and help was enlisted when needed, but for many years the community provided enough experience, knowledge, skills, common sense and tenacity to deal with the festival’s business. Additionally some companies seconded staff. The “small paid staff” is a reference to the early days, when the only permanent support was a secretary working half time.

A survey reported in 1983 that there were about 700 volunteers. Half were engaged year round in organising and administering the myriad tasks needed each year: selling tickets, sorting hospitality and accommodation, book-keeping, arranging publicity materials and events, fundraising.

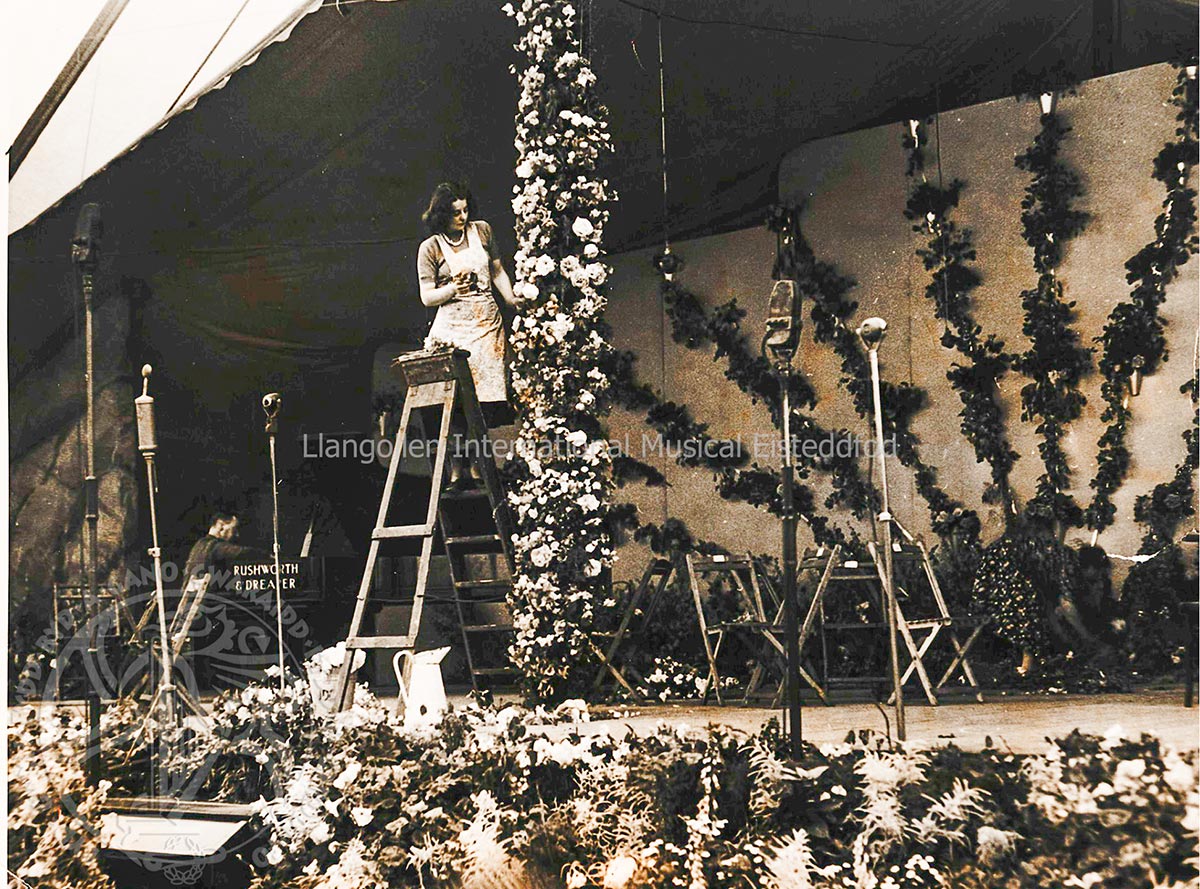

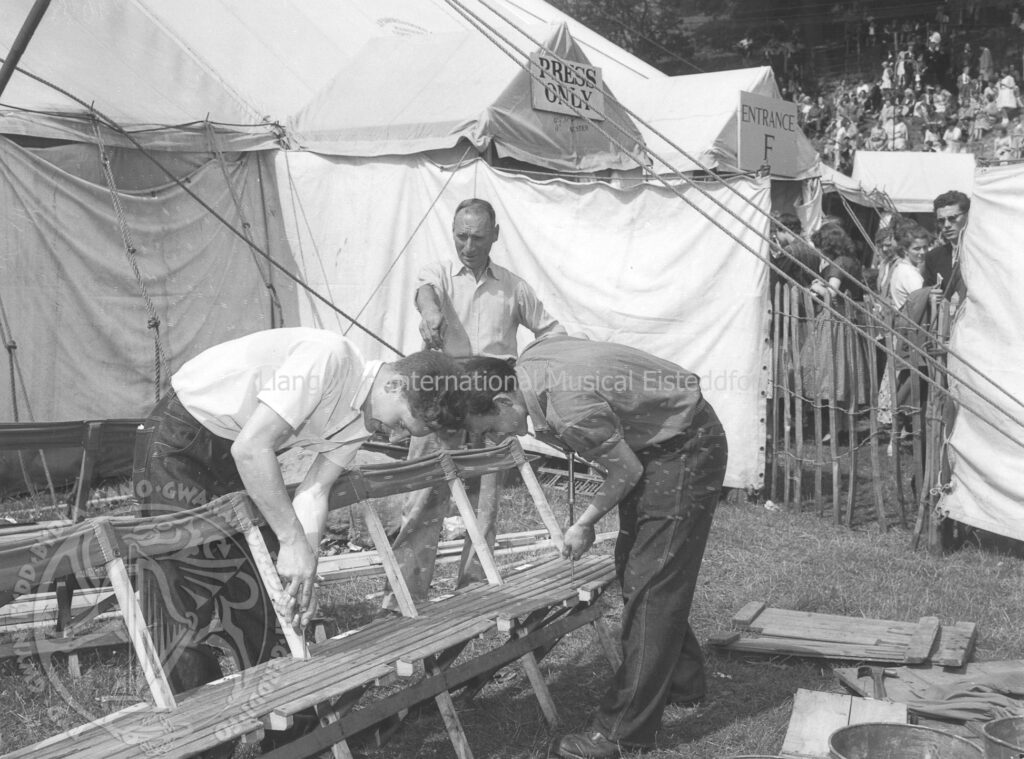

The other half became involved around the time of the Eisteddfod; setting up and furnishing the tents; installing and refreshing the floral displays;

staffing the ticket booths and information tents; translating for competitors; stewarding; children as messengers and programme sellers, adolescents as ushers; supervising car parking; and taking it all down again afterwards, and putting it away.

The volunteer army formed the main interface between the Eisteddfod, the competitors and the paying customers.

The scale and scope volunteer activity helped create a large local community supporting the Eisteddfod, and a strong communal spirit. It seemed like every family was involved. Lord Trevor, an enthusiast, rode to help every yearon his tractor. The excitement in June when the marquee was being put up was palpable throughout the town. There were always grumbles about committee meetings stealing the evenings, but the outcome – the joyous June or July week – was by far the highlight of the year in the Dee Valley, and people felt a source of real pride for their contributions.

Just like it allowed competitors to assert their choice of national, regional or cultural identity, the Eisteddfod encouraged volunteers to introduce and develop their own ideas to support the festival. Successful initiatives include the souvenir brochures designed in the 1950s by Mr Longley, a talented multilingual translator who worked for ICI; the Philatelic “Society”, which for 20 years produced attractive First Day Covers which helped spread news of the Eisteddfod round the world; and after the Millennium pre-concert talks, which brought competitors, adjudicators, historian and the like to educate the audience about mysteries of the Eisteddfod, and also usefully filled a gap in the day’s programming. Encouragement was certainly given, a little financial support maybe, but it was up to the innovators to find in the community other volunteers who wanted to help with their ideas.

Volunteers were organised into committees, five for the first Eisteddfod, peaking in the 1990’s at over a dozen. The Eisteddfod’s structure which was both hierarchical and highly functional: each committee had a recognisable part to play.

By 1948 the organisation had settled down (see a Membership Card from 1948). The chairs of the committees, and a few other officers, assembled as an executive committee, assisted by an executive secretary; for many years the secretary was Bert Reeves, a senior manager seconded by the first president, Clayton Russon, from his Llangollen business.

Above the executive committee was a large Standing Board, elected every year at an open meeting. After the Eisteddfod incorporated as a limited company in 1974, the open meetings became company general meetings, and were much tamer.

The cost of the Eisteddfod can be measured not just in pounds sterling, but in the hours spent on the phone and the typewriter, the evenings spent in committee meetings. Dylan Thomas famously said of the Eisteddfod “Are you surprised that people still can dance and sing in a world on its head? The only surprising thing about miracles, however small, is that they sometimes happen.” Well, to find the saints and angels who performed the miracle at Llangollen look no further than the volunteer community.