In June 1947 a small troupe of Spanish musicians and folk dancers played and danced in Llangollen during the first international eisteddfod. The response from the audience to their performances was so enthusiastic that the nascent festival expanded its remit; it would no longer just be choral. In 1948 competitions for folk choirs and folk dance groups were introduced, with the dancers, singers and accompanying musicians wearing their national costumes, and very quickly became the defining characteristic of the early Eisteddfod. By 1957 the two competitions attracted close to 100 groups, and the competitions ran through to 10.30 p.m.

Despite the impact both on the 1947 event and on the subsequent growth of the Eisteddfod, most histories have given very little information about these first Spanish performers: who they were, where they hailed from. As to why they came to Llangollen, chance and serendipity are stressed: they turned up by accident hoping to compete. The dominant story has the Spaniards on a tour of the UK organised by the Esperanto Society, who contacted Music Director W. S. Gwynn Williams offering participation by the Spaniards, an offer he accepted and in so doing created the successful new direction for the Llangollen Eisteddfod. Even into the mid-80s a former chairman emphasised the great risk the Eisteddfod took in allowing the performances; he said “we didn’t know how good they were”.

All this is utterly wrong. The true story is that since no Spanish choirs were able to attend, the dancers were a planned substitute. The Archives reveal a frantic correspondence in May 1947 between Llangollen and Madrid; the Eisteddfod organisation deliberately invited a highly regarded Spanish folklore troupe to Llangollen as a way out of a difficult situation.

Here are the details of what happened.

Working through its representatives in British embassies, the British Council supported the Eisteddfod in 1947 by finding choirs in many countries who might compete in Llangollen; they also took on the distribution of sheet music to the choirs, so they could learn the test pieces. Getting this paperwork out didn’t go with uniform efficiency, however, and there were delays especially in Budapest and Madrid. The Llangollen end of this operation was handled by Harold Tudor, Publicity Director and a principal instigator of the festival, who worked part-time for the British Council.

In May 1947, one application from a Spanish choir had been accepted, and was included in the programme. Then just four weeks before the event was due to start, came a message they were withdrawing because they’d not had the musical scores for long enough to practice fully.

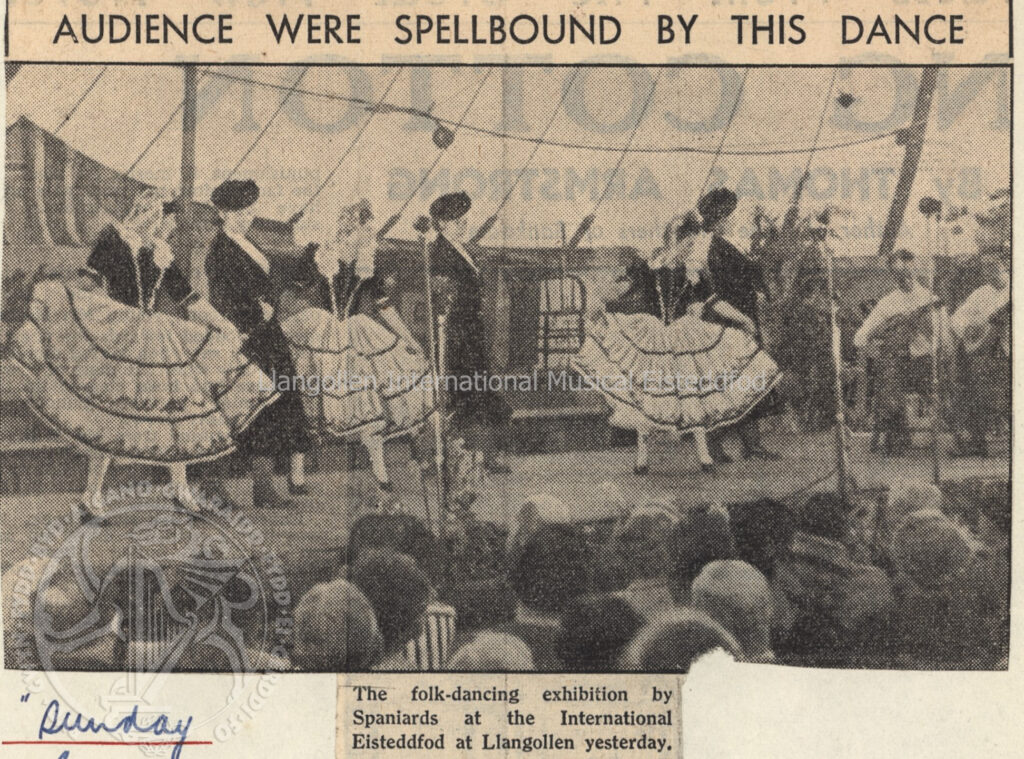

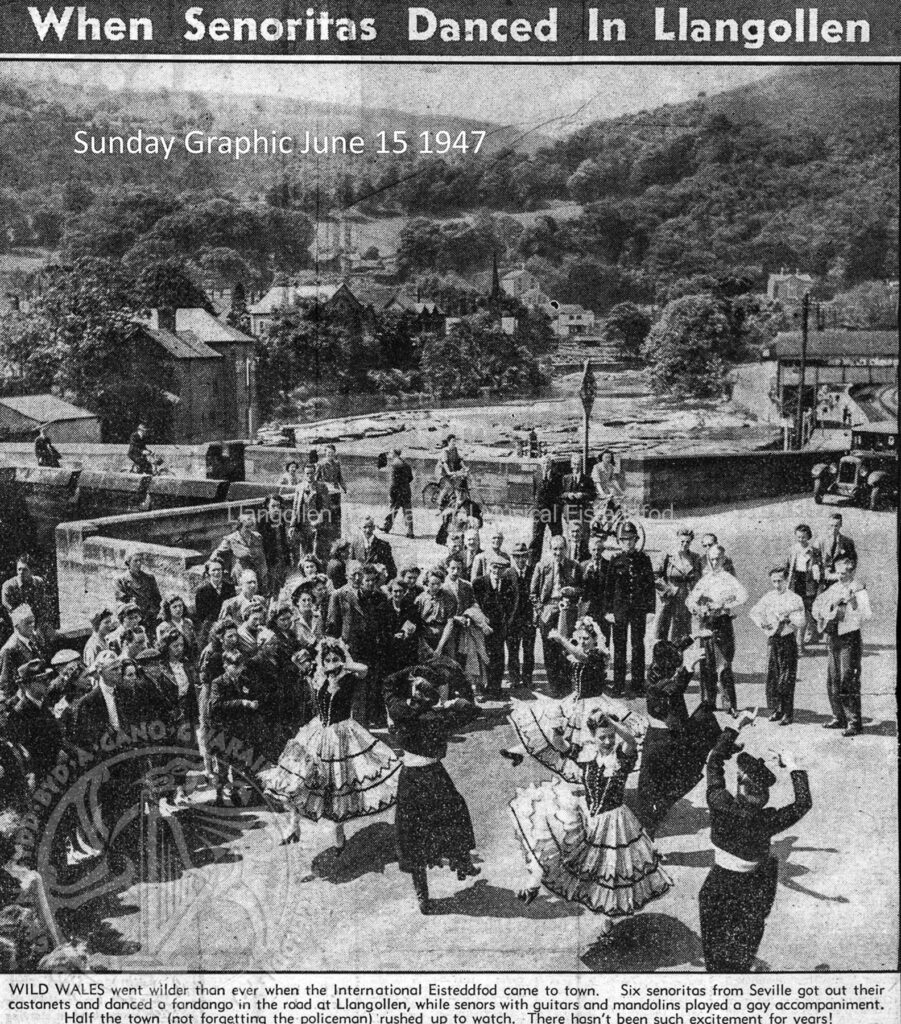

Mrs Marjorie Munden, working with the British Council in Madrid, suggested the alternative of folklore musicians and dancers from Seville and San Sebastian with an assured reputation: the troupe was led by Otero de la Gandera. Tudor quickly acquiesced, the Eisteddfod organisers endorsed the groups’ last-minute application for visas, accommodation with families in Froncysyllte was arranged, there was a formal welcome on Llangollen Station, and the first performance on the Eisteddfod stage was on Friday June 13 1947. The dancers from San Sebastian gave a programme of traditional Basque dances, accompanied by the music of the chiscus, an instrument resembling a recorder. The Seville team danced fandangoes accompanied by lute and bandurria.

The rest is history. The Eisteddfod was transformed.

There are however a few blank spaces in the story, enticing the historian to fill them with hypotheses and suppositions. We can envisage for instance that the organisers’ desire for a Spanish contribution was to engage with Europe’s largest remaining fascist state, since the express purpose of the festival was to promote better international relations by making contacts between ordinary people.

The vagueness in the Eisteddfod’s explanation of the Spaniards’ appearance can perhaps best be put down to a wish not to embarrass the British Council who were considered essential to its Eisteddfod’s future, at a time when Llangollen was being acclaimed on all sides.

Finally, we don’t at present know much more about the troupe. Sadly, our searches have yielded no information about the leader or the intermediary in Madrid who made it possible.

© Chris Adams 2022