The founders of the Llangollen Eisteddfod dearly wanted to foster reconciliation among the recently warring nations of Europe, and no event in the history of the festival so marks the successful achievement of this aspiration as the first participation by German competitors in 1949. An Italian choir had come to the first Eisteddfod, there were Austrians in 1948, but everyone knew that Germany would be the big test of the theory behind the Eisteddfod.

Most accounts of this German visit begin and end with Hywel Roberts (“Hywel Bach”), then in his first year as a stage presenter. Faced with compering Friday’s mixed choir competition, what could he say to introduce Volkshochschulchor Lűbeck, remembering as he did that four years earlier his brother had been killed on German soil on the last day of World War II? His appeal to the audience to “welcome our friends from West Germany” produced minutes of cheers and tears, delaying the progress of the mixed choir competition for many minutes. It also created a lasting friendship that culminated with Hywel Roberts being made a freeman of the City of Lűbeck in 1988, just before his death. A lovely Eisteddfod story.

But as always it is worth digging a little deeper, before and beyond the formality of the Eisteddfod stage. The display of the generous spirit of the Welsh audience and presenter that we celebrate so often only gave public voice to a welcome that had begun days earlier – on Llangollen Station – and involved many people in the town. It included the flag raising ceremony on the Wednesday, in which the choir participated with the Eisteddfod chairman – probably the first occasion on which the new German Federal Republic’s flag had been flown in Wales.

Moreover, Volkshochschulchor Lűbeck was playing its own distinct role in the post-war movement to seek rehabilitation and reconciliation through music. They merit a mention for what they were doing in Germany, not just because they came to the 1949 Eisteddfod.

This is the story of the first Germans to visit Llangollen after the war…

Lűbeck fell within the British Zone of occupied Germany, and the choir had been formed with encouragement from the British administration: under its conductor Lebrecht Klohs, its mission was to work with the thousands of refugees billeted in camps and halls around the city, especially the women and children who had suffered the worst feral atrocities of the Russian triumph in East Germany. The choir – based in a local Hochschul – were taught how to train and conduct other choirs and musical groups formed in the refugee community. Most of the choir were themselves refugees from the East, as was the conductor. They were young, few of them over 25, and included apprentices from many trades, returning prisoners of war waiting for the universities to open again, a few teachers going through the process of “de-Nazification”, a typical collection of young people for this period of German post-war society.

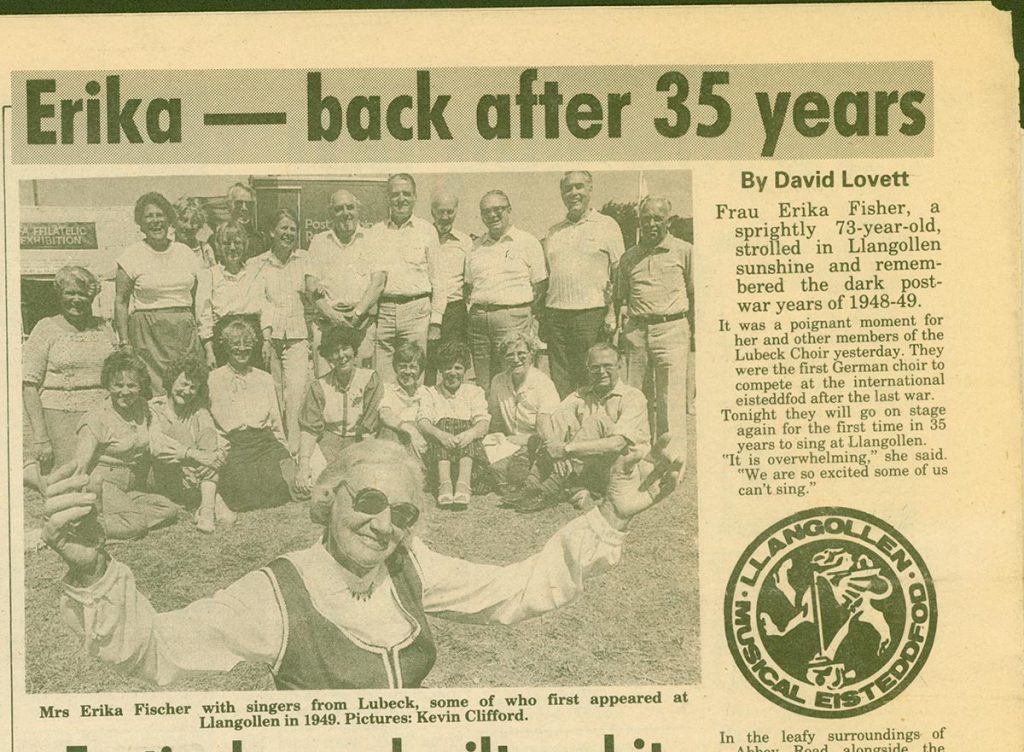

It was a Captain Cripps, a youth officer in the British Occupation Administration, who suggested that the choir apply to compete in Llangollen. He was based in Kiel, fifty miles from Lűbeck, and the choir’s organiser Erika Fischer frequently cycled between the two cities to make progress with the arrangements. The choir members rehearsed hard; they constructed costumes from scraps; badges with the black, red and gold colours of the new Federal Republic were used for decoration. The money for the trip was accumulated pfennig by pfennig. Even with official support, passports for foreign travel were hard to obtain, and foreign currency for the journey was bought illegally on the black market.

Travelling to Wales was an exciting adventure. And as the choir’s train left the Lűbeck station. they realised that Erika Fischer, carrying the precious ferry tickets and British money, had been left behind; she joined up with the choir a couple of stops on, after a frantic car chase.

As their train puffed into Llangollen on the Monday of Eisteddfod week, the 25 choir members were tired, hungry – they had been eating sparingly during the weekend’s travel to conserve their funds – and increasingly apprehensive: the platform was packed with people! What kind of reception would there be? Was this a hostile demonstration? The nervous men encouraged the ladies off the train first, but quickly followed when they saw what awaited them: hugs and kisses from the Eisteddfod volunteers assembled to greet them, followed by sandwiches and cups of tea from Hospitality Committee in the chapel opposite the station. The inevitable tears flowed all week.

The choir was accommodated in Plas Geraint, and also had a couple of days in the Youth Hostel. Writing later, they fondly remembered the hospitality of the townspeople, especially the high quality of the tinned salmon sandwiches made with “wonderful” white bread at the Tyn-y-Wern Hotel. Some of the female members of the choir enjoyed days out with young Welshmen, though it was roast beef and Yorkshire pudding in Rhyl that seems to be the most enduring impression of these jaunts. The town organised a farewell concert in the Town Hall, which raised over £30 to help pay for meals and accommodation on the homeward journey.

The “Lűbeck Choir” took part in the International Eisteddfod many times during the next 40 years. They never won first prize in a choral competition, but they will never ever be forgotten in Llangollen.

Sources: Papers from the Lűbeck Choir in the Eisteddfod Archive.